Granddad liked to draw with me. When my father was in Occupied Japan with the Army, Mom and I stayed with her parents in Southern California. That’s probably the time Granddad and I drew together. Maybe not the only time. I don’t remember a lot of back then, as I was only two, going on three. But I feel there is truth to much of what I heard. I sort of remember his large hand patting my back, giving my hair a mess-up, and then calling Mom and Grandma over to see what I did.

Dad came home from the Korean War badly wounded. The best thing was, the three of us were together again. I started school in Central California, and a few years later we moved north to be closer to Dad’s family in Southern Oregon. As far as I know, Granddad died a year or so after that. The folks did not talk to me about it. I went to stay with my Aunt May and Uncle Ivan on their farm in Looking-glass, while Mom and Dad drove south to attend the funeral.

The relationship between Granddad and me was not very current by then. We saw one another rarely. Once or twice, while he was still alive, the folks and I would go down Highway 99, from our home near Roseburg, to Menlo Park or Hayward, where Mom’s siblings lived – and all my cousins. The grandparents would drive up from Santa Barbara and we’d have Easter or Thanksgiving. Granddad and I may have sketched together those few times. If so, Mom would have commented to the Gathering that Granddad had been drawing with me since I was very little. She would have said that the two of us “go off into our own world” when we are together. Granddad and I sat side by side at the table, “just going to town”, as Mom would say.

Grandmother lived on for several more years. I remember her coming around occasionally after my brother was born, even as he started school, which is when I left grammar school to enter junior high. At my junior high school in Southern Oregon there was a very good arts curriculum. I took classes in pottery and copper enameling. We moved a couple of times before I finished high school. Dad was often restless. My Junior year of high school was spent in Northern Oregon, where I showed my drawings to an administrator and was accepted into the arts program for the following year. However, before that happened, we moved on to Southern Washington, and I entered a school that did not have drawing or painting classes. That turned out to be fine with me. I was busy enough painting stage settings, and contributing to the steady stream of butcher paper pep rally banners my senior year.

A business minor in community college was something I “could someday fall back on”. Mom again. I took Art to practice art. Business proved to be terribly dull and simplistic to my highly charged imagination and romantic sensibility. I switched to Literature as a minor, realizing how much I love stories. My Dad had a little bit to do with this decision. I grew up listening to his stories. I learned that he was at least a 2nd generation storyteller. And when his war wound limited his physical activity, he took the time and had the ambition to turn to writing professionally.

Upon my return from a drafted enrollment in the Army, and fortified by the G.I. Bill, I became an Art major at a state college in Northwest Washington. As I advanced to and through my senior year, Drawing became my favorite subject. I took a number of classes from the dynamic Robert Jensen. It was his “Inventive Drawing” class that became the final class of my final year at college.

A student of geology and I shared an A-framed house then. It was far from the hustle and glitter of the college and city. We lived beside a lake in the woods. It was mostly quiet and we were somewhat isolated. We went out on the nearby road and tried to hitch-hike when the car would not start. Some mornings a woodpecker came and had a go at our roof. The nights were dark, with only the sounds of wildlife like owls and frogs.

I had been producing graphite drawings of trees and forests. The pencil seemed to be good for only intricate stuff. That kind of bugged me. I could articulate the details of boughs and leaves, twisting branches and roots, boulders or splashing water with my pencil, but when it came to sky, clouds, or broad surfaces where I thought cross-hatch shading would further actualize the scene, it never worked; the overall ‘light’ began to choke.

‘And this style is all too freaking tedious for me!’ I fumed, exasperated. It was the night before the final critique of my college career. However much I wanted to moan about it, I would be required to stay up late finishing my project.

I occupied the upper part of the “A” in our A-frame. The peak of the house was just above my head. In my work space the ceiling angled away to each side of my table. I relied on an elbowed office lamp for light. The paper was a heavy, cotton base Arches. The pencil; probably a 5B. The picture was half the way finished. The roommate was gone for the night, so there was nobody around but me. I settled in to advance my pencil-dance across the soft, snow white surface, as snow white as a 60 watt incandescent could make it. As I worked, I thought the thoughts of my sort of 25 year old self.

Out of nowhere, beyond any reason or rhyme I had, I was suddenly aware of a head hovering next to mine, its face I immediately recognized to be Granddad. It was like he was bending to look at my work, or working on his own drawing next to mine. The instant I pulled together what was happening, as heart stopping alarm passed through me, the apparition was gone.

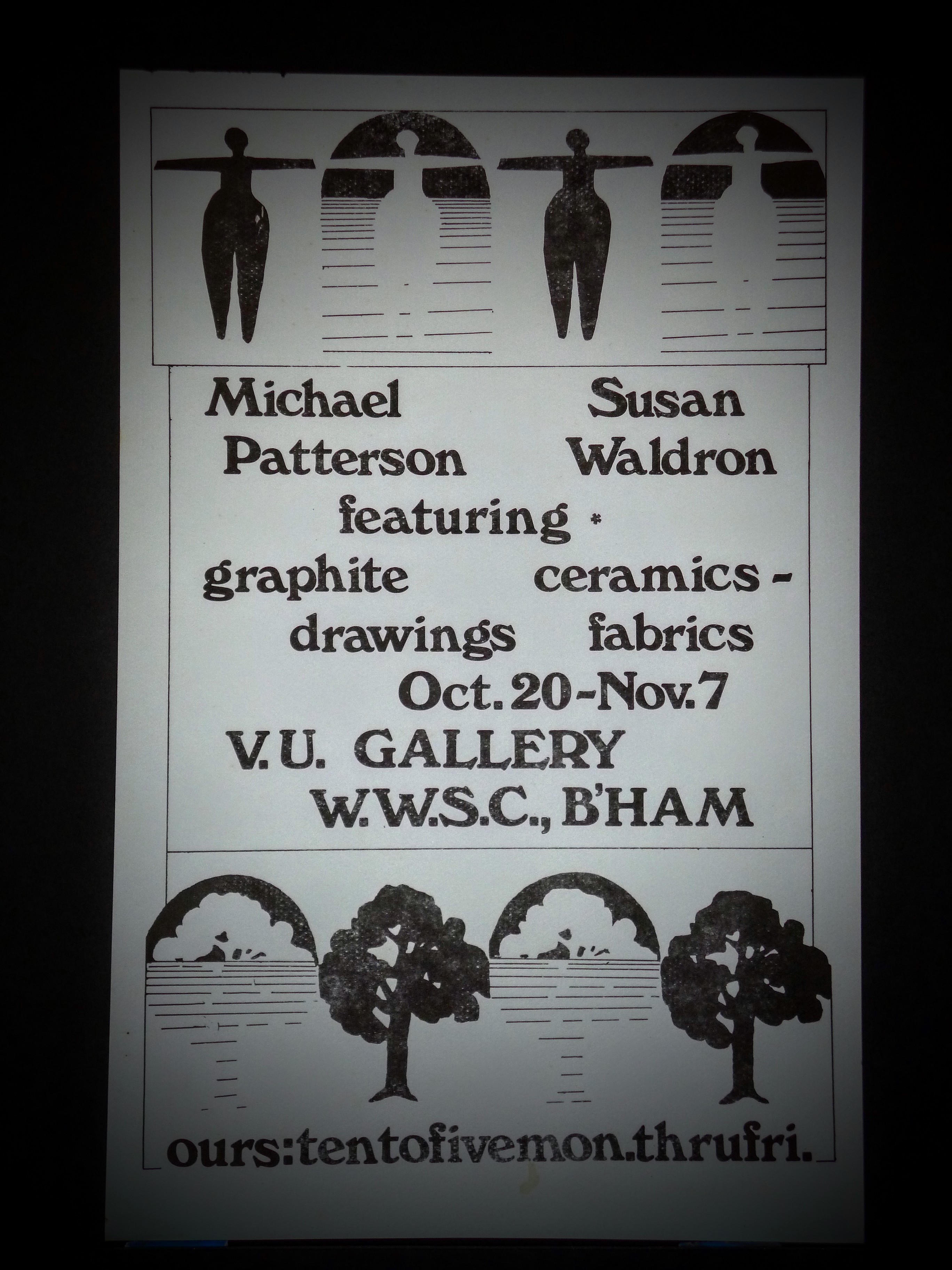

Makes one wonder. I finished the piece and presented all my work on time the following day. It was a hit! No one had seen anything like that from me before. Jensen got excited about it. Not much time after that, I teamed with a fellow art student, Susan Waldron, and we hung our work in the school’s gallery. One of my pieces was selected for purchase for the college’s collection.

Even more unforgettable was the visit, apparently from Granddad, that I had during the night before the critique. By that time, I barely remembered the man. Yet I recognized him right away, as if we were fresh from the past. I decided Granddad didn’t mean to be spooky. I think I experienced his influence in a pure form by this encounter. Interesting question: How much can he take charge of my work? He is an ancestor, so his claims on me are not deniable. Nevertheless, he, or both of us, seem to live where perpetuation of idea thrives, and he, or we, decided to meet at that particular moment. Summarily, this suggests the possibility of a rich and different spin to the title, “Granddad Liked to Draw with Me.”

Poster I designed for the show